This guidebook focuses on the Benchmarks Model and its application in professional psychology training programs. It is intended to complement the brief practical introduction offered on the main page of the Benchmarks Evaluation System. The first section of the guidebook introduces the benchmarks model, and discusses how graduate or internship programs can move quickly to adapt the rating system to its current training goals. This section also discusses some of the issues that programs have encountered in implementing the rating forms, as well as offering some suggestions about sharing competence evaluations with students, and creating remediation plans for students who do not reach required levels of competence. A separate evaluation form dealing with the relationship competency is also described. The second section discusses how a more thorough implementation of the competency-based approach to education and training can be understood and implemented. The second section of the guidebook discusses issues involved in the full realization of a culture of competence in graduate education and training.

The guidebook was compiled by a work group, whose work was sponsored by a grant from the Association of States and Provincial Psychology Boards Foundation and the APA Education Directorate. This document has not been voted on by the APA Council of Representatives and does not represent the policy of the American Psychological Association.

Work group members included: Linda Campbell, PhD, Nadya Fouad, PhD, Catherine Grus, PhD, Robert Hatcher, PhD, Kerry Leahy, PhD and Steve McCutcheon, PhD

expand all Introduction to the benchmarks modelEvery program wants to produce graduates who are competent to provide effective professional services, and who strive for excellence in their professional work. The competency approach is intended as an aid to help programs realize these goals.

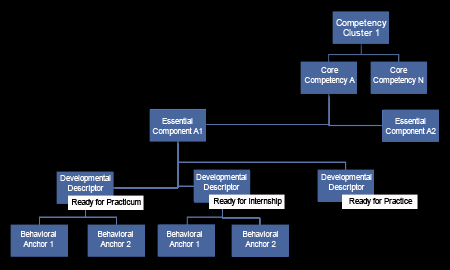

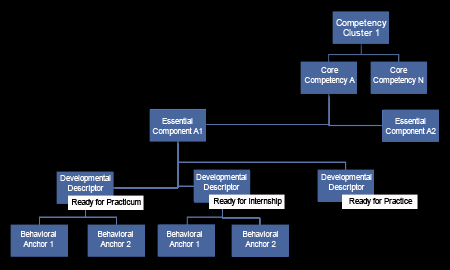

The Competency Benchmarks for Professional Psychology document delineates core competencies for professional psychology that students will develop during their training. The benchmarks document articulates and organizes these competencies in a nested framework (see figure below; see also the revised benchmarks).

Six clusters (professionalism, relational, application, science, education, systems) provide the overarching structure for the benchmarks. Within these clusters, 16 core competencies are nested, each of which contain several essential components with corresponding developmental descriptors and behavioral anchors delineated for each of the three stages in the education and training sequence.

The content of the Benchmarks builds on several decades of work to identify core competencies in professional psychology. This work has, in large part, been in response to theincreasing calls across higher education for accountability and outcomes-based instruction. The identified competencies and the specific language in the document were developed and modified through an iterative feedback process that included a broad group of constituencies within the education and training community in professional psychology over a period of several years.

The benchmarks is intended to be a resource for education and training programs in professional psychology to assist in the development of curriculum and the assessment of trainee learning outcomes. It is not intended to set requirements for programs. In recognition of the diversity of settings and training emphases within the broad domain of professional psychology, it is expected that training programs will customize components of the document (e.g., behavioral anchors) to reflect program-specific goals.

Implementing the benchmarks evaluation systemThe Benchmarks Evaluation System sought to transform the content of the Benchmarks document into a useable instrument for assessing and tracking students’ competence during their training in professional psychology. It is generally recognized that the original Benchmarks document itself is too large and extensive for use as a tool to rate student competence. For example, it is broadly inclusive of the full range of professional competencies, some of which may not be relevant to a particular graduate or internship program. In its focus on the evaluation of student competencies, the Benchmarks Evaluation System fulfills a need that most programs have to evaluate and document student progress toward program goals. The system provides an immediately accessible approach for examining your program’s current training goals, and mapping them onto the Benchmarks evaluation forms. These forms can then be used to evaluate students’ progress toward your program’s goals. We believe that this approach can also help programs gauge their interest and readiness for a broader implementation of the competency-based approach, which is discussed in the second section of the guidebook.

The Benchmarks is not intended to be implemented as a fixed model, and accordingly the Benchmarks Evaluation System is designed to be used in a flexible way to tailor a set of competency expectations and rating forms that represent the goals and learning outcomes of a particular training program.

Modifying the Benchmarks to a particular program involves the following process.

We stress again that programs are free to develop additional individualized essential components and behavioral anchors that characterize the program’s curriculum and identity.

Example: Consider an internship program in a large Children’s Hospital in an urban setting. The program chooses the clusters of professionalism, relational, application, science, education and systems.They choose all of the competencies under each cluster, except for teaching in the education cluster, and the management and advocacy competencies under systems. Further, they choose all of the essential components except for scientific approach to knowledge generation under science. They had considerable discussion about whether or not expecting students to develop competencies in producing research, but came to consensus that with the time limits and expectations of clinical hours at the hospital, they cannot expect interns to develop that competency.

The faculty then develops a set of behavioral anchors for each essential component at the readiness for entry to practice level that is particularly geared to working with children and their families. In addition, the faculty identified particular competency areas that they wanted students to end the year with very high levels of demonstrated competence that corresponded to their work in an urban academic hospital: individual and cultural diversity, evidence-based practices and interdisciplinary systems. To that end, they identified behavioral descriptors that conveyed that high level of competence in those competence areas.

Choosing the evaluation form . For ease of use, the Benchmarks Evaluation System offers the option of an overall form that applies to all levels of training, and as a set of three forms, one for each developmental level. The overall form takes a wide developmental perspective, assuming the possibility that a given individual may be considerably above or below the level generally expected at their level of training. The overall form offers an unconstrained range of rating levels, allowing description of competence at levels below and above those assigned to the student’s level of training. For example, a practicum student who has exceptional competence in individual and cultural diversity may be better described using the “readiness for practice” level than the “readiness for internship level.” The disadvantage of the overall form is that it has three times as many developmental descriptors for each essential component, and is therefore longer and harder to use by supervisors or instructors. Since a key goal of the Evaluation System is to make competency rating feasible, it also offers three additional forms, each corresponding to the one of the three training levels. These forms are easier to use, and we recommend them for regular application. In this case use of the overall form may be indicated for initial competence assessment prior to entering a new training level, or in cases where particular strengths or weaknesses are detected and need to be tracked.

Using the rating scale . Examining the overall evaluation form, note that qualitative differences in competency standards are suggested at each of the three levels (increasing competence across levels moving left to right). Within each level, using either the full form or the level-specific form, the rating scale is used to indicate how characteristic the competency description is of the trainee’s behavior. The rating scale is a 5–point Likert scale ranging from “0” (“Not at All/Slightly”) to “4” (“Very”). The scale requires that raters judge the match between the competency description and the trainee’s behavior; thus, raters are not asked to make an additional quality or preparedness judgment. This approach is intended to help raters maintain focus on observed behaviors, and to reduce the inflationary influence induced by making broader or more critical judgments (e.g., “meets expectations,” “excellent/outstanding” vs. “average,” etc.).

For each item, raters should select the number corresponding to how characteristic the competency description is of the trainee’s behavior. If the individual being rated is best described by a “0” or “4” on any individual item (indicating that the individual has not yet demonstrated the behavior or always demonstrates the behavior reflected in the item, respectively), the rater using the full form has the option of rating that item at the level below or above the individual’s training level in order to provide the individual with additional information regarding their achievement of each competency. Otherwise, the rater should request a full form, or use the narrative section at the end to detail the issues involved. At the end of each evaluation form, raters have the opportunity to write a qualitative narrative summarizing the trainee’s current level of competence and describing the trainee’s strengths and areas for further work.

Setting competence expectations . The minimal expected competence rating for each competency is the program’s decision, rather than that of an individual rater (e.g., a supervisor). The supervisor is not asked to determine whether or not a trainee showing the specified level of competence meets competence criteria. For example, a program with a strong emphasis on multicultural counseling might expect the essential ICD component “Monitors and applies knowledge of self as a cultural being in assessment, treatment, and consultation” (2A) to be evident in the first two years of training, and to expect the behavior to be “very” characteristic of trainees. Trainees meeting a program’s criteria for competence should progress to the next level (e.g., “readiness for internship”), whereas those who do not, should participate in a remediation program (see section below on Remediation Plans for guidance on developing an effective plan for trainees with competency problems).

Familiarizing faculty and supervisors with the evaluation forms . Although it is optimal for the faculty and supervisors who will use the rating forms to participate in developing them, it is often the case that, for example, supervisors who have no prior acquaintance with the competencies approach or with using a competencies rating form will be asked to complete a form. If it is possible to gather the supervisors together for an introductory meeting, it is a good idea to present the rationale for the approach and to describe how their work with evaluating trainees plays a crucial role in the operation of the program. Using real (and disguised) or hypothetical examples, the group can work to transform a narrative assessment of a trainee into ratings on the scale. A meeting of this sort should also allow supervisors to raise questions and concerns about the competencies approach, about the scale, and about the practical issues involved in using it. If a meeting is not possible, then a letter, a phone call, and/or referring them to this website may help in orienting the supervisors. We have found that supervisors unfamiliar with this process may be helped by a phone call from a knowledgeable faculty or staff member, in which they are walked through the process of applying the form for a particular trainee they are working with.

Orienting trainees to benchmarks and methods of evaluation . Trainees should be oriented to the program’s competencies, means of evaluation, and competency expectations at the start of their training, and at relevant transitions (e.g., before starting practicum). At the inception of an evaluation period for a benchmark (e.g. introduction to assessment), the instructor and/or training director should introduce the trainee to the Benchmarks, the relevant essential components, the developmental descriptors, and their behavioral anchors. This orientation prepares the trainees to be focused on the learning objectives for the experience and to be self reflective about development of the skills involved.

Objections to the evaluation system . In the course of orienting faculty or supervisors with the competencies benchmarks rating forms, a number of objections to them have arisen. We will briefly discuss these objections to assist in the orientation process.

We have found that this can be true if the form, and the valuable role is serves in the student’s training, is not discussed with the supervisee at the very start of the supervision. If the supervisor regards the competencies approach and the form as an intrusion, of course this will affect how she presents it to the trainee. However, if the supervisor goes over the form and uses it as a way to talk about what she and the trainee will be working on during their time together, and if the supervisor uses the form regularly to praise the trainee for areas of growth, and to work with the trainee on areas that need more attention, then the trainee will generally find a good deal of comfort in the clear expectations voiced by the supervisor and the ongoing sense of the progress she is making toward the goals of the supervision. Of course, in these discussions, the supervisee’s own input is key – what does she want to gain from the supervision? Where does she think she is in terms of the goals at this point in time? In other words, if the rating form can become a part of the collaborative relationship, then it will be much less likely to be experienced as an intrusion by the supervisee. We have found that it is easy to overlook how concerned trainees are about their supervisor’s expectations, and how worried they are about critical evaluation of their work. Rating forms, and a good discussion of the competencies they are meant to assess, can help by making these expectations explicit, and by voicing the supervisor’s evaluation. This evaluation so often remains implicit, to be filled in by the trainee’s own overly-active sense of deficiency as a novice in a complicated field.

Communicating competency evaluation results to trainees. Competencies that have been assessed with the Benchmarks Evaluation System may be utilized for formative or summative evaluations or both.

Formative evaluation. Formative evaluation is offered regularly during the ongoing training process, and is intended to help the trainee understand where she is in the process of developing professional competencies – to understand how and where she is gaining competence, and to locate areas that may need more attention. Trainees may be encouraged to self monitor during the learning experience and to be aware and document their observations of their own learning experience. Trainees may meet with the faculty instructor or supervisor periodically to discuss self evaluation of their competency development and to receive feedback from the faculty instructor. The formative approach allows trainees to make corrective adaptations while still within the learning experience rather than possibly spend weeks in a semester before corrective action. The disadvantage of ongoing evaluation is the time demand for the faculty or supervisors and trainees. The ongoing self monitoring aspect for trainees, even though time consuming, is especially beneficial to the incremental development of skills.

Summative evaluation. As its name implies, summative evaluation provides an integrative overview of the trainee’s skills at the conclusion of a period of training. The Benchmarks Evaluation System tends to blur the distinction between formative and summative evaluation, because it does not ask the evaluator to determine whether the trainee’s performance meets predetermined criteria for adequacy, which is a common feature of summative evaluations. A full summative evaluation would be the result of comparing the evaluator’s ratings with the criteria for adequate performance established by the training program. Thus a faculty member or supervisor may offer a final formative evaluation, and the program director may offer a final summative evaluation after matching the faculty or supervisor’s ratings with the program’s criteria for adequate performance. This task may be assigned to the faculty or supervisor, however, in which case the final evaluation will be summative. As noted above, however, this dual task may reduce the validity of the faculty or supervisor’s ratings of the trainee’s performance.

At the start of the training experience, the program director is encouraged to review the evaluation form that will be used for the final evaluation with the trainee, who should also be informed of the expected levels of competence for acceptable performance. Having clear expectations for what is to be accomplished during the training period is very important.

The value of evaluation is enhanced when trainees are asked to rate themselves on the evaluation form at the start of the training experience. Reviewing these self-evaluations with the faculty or supervisor at the start of training can also help both trainee and supervisor develop more focused goals for the training experience. Comparison of these self-evaluations with a repeat of them, and with faculty/supervisor evaluations, can help trainees see the progress they have made, identify areas in need of further work, and enhance their own self-reflective skills through comparison with supervisor ratings.

One of the benefits of the Benchmarks Evaluation System is that its focus on competencies can help quickly to identify competency problems. It is extremely important that a program have a documented plan for addressing competence issues, rather than making up a plan at the time that a trainee shows evidence of a competence problem. As part of this plan, the competencies rating forms can help pinpoint and document a trainee’s competence problem, and may point to steps for remediation. Continued evaluation using the forms during remediation help document the trainee’s progress (or lack thereof), and support further administrative action should it be needed. To aid this process further, a model Competency Remediation Plan and other resources are available.

Ethical guidelines require that efforts to resolve conflicts and problems must first be made informally, so it is critical that any competency concerns are first discussed with the trainee. Once a competency problem is identified, it is recommended that all relevant parties come together in a remediation meeting. The plan includes noting the date and names of the trainee, faculty, and supervisors. The competency domains of concern are noted (identifying one or more of the 16 competency areas), in which the trainee’s performance does not meet the benchmark required by the program. The plan then documents the description of the problem(s) in each competency domain with as much specificity as possible, the date it was brought to the trainee’s attention, and steps already taken to address the problem by both the trainee and the faculty/supervisor. The plan then documents the specific expectations for acceptable performance, noting the trainee’s responsibilities and the supervisor or faculty’s responsibilities for action. The timeframe for acceptable performance is specified, as is how and when the performance will be assessed. Finally, the plan documents the consequences for unsatisfactory remediation, if the trainee is unable to change his or her behavior.

Example: As an example, consider a student who is a 1st year doctoral trainee in a practicum class. His first journal entry notes his fear of African-American clients. His responses to ethics vignettes in class indicate lack of knowledge about the ethics code and poor ethical decision-making. His instructor is concerned, talks to him about it, but notes that the student has made no effort to focus on increasing his cultural competence or learning more about ethical decision-making. She brings her concern to the faculty for help to develop a remediation plan. The faculty identify the competency areas as ethics and individual and cultural diversity. The remediation plan included discussions with the trainee about concerns and potential harm to clients. The faculty determined that they expected him to be able to articulate appropriate responses to new ethics vignettes and to demonstrate self knowledge of what led to unconscious biases against African-Americans. The faculty decided that they would work with him in an independent study on ethical decision making and on categorization theory and knowledge of self and others. They would evaluate him at the end of the semester, and the consequences of failing to demonstrate competence were determined to be probation or expulsion.

As part of the work of the benchmarks workgroup, an evaluation form focusing on the relationship competency was developed that gathers and organizes all references to relationship competencies in the benchmarks document, yielding a more specific and expansive set of essential components than those found in the relationships competency in the benchmarks rating forms. Faculty instructors or directors of training may consider utilizing the more expansive version of this competency if (1) the program values greater or more specific relational development or (2) the program encounters trainees who are having particular difficulties in relational skills with faculty, peers, supervisors, or clients. Trainees with competence difficulties are often reported to have particular problems with relationships. The more detailed Relationships Competency Rating Form can help specify and document these difficulties, and can help in monitoring the effectiveness of remediation plans for these trainees. If the more expansive form is used for routine assessment of competence, it is recommended that the formative approach be utilized with this competency given the difficulty of teaching relational competency and the importance of specificity, examples, and direct guidance for trainees.

Implementing a competency-based education and training programThe Benchmarks Competency Evaluation System is designed to help programs evaluate, track, and document the competencies the program expects its students to achieve. This system is a key component of a broader approach to competency-based education and training in professional psychology. Applying the Benchmarks Competency Evaluation System is a useful step towards establishing a competency-based education and training program. This section offers an overview of the broader competency-based approach to education and training, based on the Benchmarks Model.

The Benchmarks Competency Evaluation System is designed to help programs evaluate, track, and document the competencies the program expects its students to achieve. This system is a key component of a broader approach to competency-based education and training in professional psychology. Applying the Benchmarks Competency Evaluation System is a useful step towards establishing a competency-based education and training program. This section offers an overview of the broader competency-based approach to education and training, based on the Benchmarks Model.

Every program wants to produce graduates who are competent to provide professional services, and who strive for excellence in their professional work. The competency approach is intended as an aid to help programs realize these goals, and the recommendations and solutions offered by this approach reach into many areas of education and training in professional psychology. Many of these recommendations involve ways to make training goals explicit, bringing them to the forefront in everyday educational activities.

First, the competency approach asks us to reconsider the goals and desired outcomes of our programs: what are the components of competent professional practice that we see as essential? What knowledge, skills, attitudes, and behaviors do we see as comprising an effective, competent graduate of our program? These goals are often articulated for accreditation purposes, and the competency approach asks us to return to considering these goals in more detail, with a focus on the competencies we want our graduates to acquire through their education and training in our programs. This process can help clarify both the overall mission and the specific goals of graduate programs, and optimally involves the entire faculty and incorporates ample input from graduates and current trainees. The Benchmarks can assist in this process, as they outline competencies that have been widely considered to be important for graduates to possess. A program can benefit substantially from reviewing the Benchmarks in light of the program’s vision of what a competent graduate should be able to do.

The next step is to examine the program’s curriculum and associated training experiences to be sure that they do a good job helping trainees achieve the competencies the program has identified as its goals. This can help programs ensure that their curricula utilize the programs’ resources most effectively. In many programs, the curriculum, the content of courses and seminars, and the training experiences have been developed over a long period of time, and are often based in part on the interests of individual faculty members. Review of these activities in light of the program’s competency goals can help focus learning on areas and material most relevant to the broader goals of the program. Faculty and trainers may wish to work together to ensure that each course, seminar, and other training and educational experience optimally addresses as many of the program’s competency goals as possible. How are attention to science and assessment built into courses on ethics? How is self-care built into the course of history and systems of psychology? Although reviews of this sort can be challenging for faculties, the process can be eased by keeping the overall goals of the program in mind, and can enhance the program’s sense of collaborating on a shared goal.

Setting competency goals and structuring the curriculum to optimize meeting these goals can be very helpful in working with individual trainees to focus and structure their path through the program and beyond. With specific, developmental competency goals for trainees, the trainees’ initial competencies can be assessed, so as to better focus the specific experiences needed to reach overall competency goals. When trainees meet competency goals earlier than expected in the course of their training, new areas can be opened up for them to expand their range of competence. Explicit competency goals can help identify when trainees fall behind, or start with a lower level of competence, and can be the basis for an explicit remediation plan designed to bring the trainee up to expected levels. All of these steps can be taken with the clear involvement of the trainees involved, who can help identify areas they feel need attention and participate in developing effective approaches to building their competence. This feature of the competency approach helps empower trainees to be more active planners and participants in their education and training, and helps form a basis for continued professional development after graduation.

The enhanced collaboration and attention to trainee learning experiences involved in the competency approach has proven to be greatly helpful to the overall tone and morale of programs across the spectrum of the professions.

A good place for a program to start would be to examine its educational and training goals, perhaps beginning with its most recent accreditation self-study, but also by reviewing its existing curriculum. Consideration during this process of the Benchmarks document (DOC, 239KB) and the APA accreditation criteria (PDF, 150KB) can help identify areas that may be in need of more or less emphasis. Redundancies across courses can also be identified this through this review.

Assessment methods appropriate to evaluate competency development in psychology trainees include portfolios, structured case presentations, written or oral examinations and objective structured clinical examinations. Each of these methods varies with respect to factors such as complexity of implementation and the specific competencies they are best suited to assess. A useful resource, the Competency Assessment Toolkit, has been developed for training programs to obtain information about assessment methods that they might incorporate into their competency evaluation protocol. The toolkit was published by Kaslow et al. (2009) and selected components of the toolkit can be found on the website.

The Competency Assessment Toolkit for Professional Psychology offers several resources that can be helpful in selecting appropriate evaluation methods. One component is a series of fifteen assessment method fact sheets, each focusing on a specific method that could be used to assess competency development in a psychology trainee. The fact sheets define and describe the implementation steps associated with the method, detail strengths and challenges of the method, and review available psychometric information. A second key resource in the toolkit is a grid that lists each of the assessment methods and notes their applicability to assess specific competencies. A third key resources is another grid that looks at the core competencies and essential components listed in the 2009 benchmarks model and provides a rating of the usefulness of each methods assess specific competencies/essential components at specific levels of education and training.

Programs wishing to enhance or introduce a competency-based approach to the assessment of their trainees may wish to consider the following suggestions:

In terms of implementation, programs may wish to select a few different types of competency assessment methods to try for formative and summative assessment. Methods selected should be based on those that have greater buy-in from faculty/supervisors, the competencies of greatest focus in the program, and consideration of available resources in the program. Programs that seek to incorporate assessment strategies that have not been used previously should consider implementing them early in the education and training sequence to build familiarity for both trainees and faculty/supervisors. The use of new assessment strategies as formative assessment tools, prior to incorporating them as summative evaluation tools may also be indicated. After new methods have been incorporated, it is helpful to obtain input from faculty/supervisors and trainees about the experience and how using the method(s) enhanced (or not) the evaluation process in the program.

A competency-based approach to trainee assessment requires attention to not only the method(s) of assessment but also to ensuring the program culture supports a culture of competency assessment. This includes support and commitment by academic leadership to the concept of assessment as a method to enhance excellence through outcomes assessment at the institutional, programmatic, and individual level. Assessment results should be viewed by academic leaders as providing an opportunity to enhance education and training programs by providing feedback about how well the program is helping trainees obtain desired learning outcomes and not take a critical or defensive stance if the program identifies need for change. In addition, incorporating a competency-based approach to assessment of trainees will be more successful when faculty/supervisors have attained competence in the process of supervision broadly and more specifically in having “difficult conversations” related to providing feedback about competence. Programs may wish to provide faculty development as part of the implementation process.

Some competencies lend themselves more to evaluation during a specific course or learning experience (e.g. assessment), through clinical supervision, or through papers or responses to questions. Other competencies lend themselves to evaluation across the curriculum and in application to professional development (e.g. ICD, professionalism). Some programs have found that competency evaluation is best accomplished through student portfolios that are evaluated periodically. Other programs may evaluate the competencies through faculty and supervisor annual feedback. Still others have capstone projects that allow trainees to demonstrate various competencies.

As noted, when selecting evaluation methods, programs should define their own minimal expected level of competence for each cluster and competency as reflected in the particular measures chosen.

It is notable that the “Readiness for Internship Level” is a much more expansive training period than the other two levels. It is likely that “Readiness for Practicum” will be at most a year and possibly a matter of weeks into the doctoral program. “Readiness for Internship” spans at least two years and possibly more. “Readiness for practice” follows the one year of internship. As a result, the essential components and behavioral anchors within the “Readiness for Internship” may be designated as early, mid, or advanced practicum in order to better identify the skill and knowledge development within the level.

Challenges (and solutions) that may arise during implementation of the benchmarks modelTo this point, the various sections of our guidebook has focused on the full implementation of a competencies-based education and training program. This section will discuss some of the obstacles and challenges that arise when moving from the ideal of a fully-implemented competencies-based program to the realities of carrying out a thorough systems change in a graduate or internship program.

We recognize that a full implementation process, as we have outlined above, may not be possible or may need to be introduced gradually for a myriad of reasons in a given program. The goal of this section is to outline the key elements of a competencies-based program, the challenges to implementation they pose, some approaches and solutions to consider, and some alternate pathways to implementation that may make the transition easier in your particular setting.

Assuming that you are in a leadership position in your program, the biggest challenge is to engage the interest and commitment of your faculty and/or supervisors in the competencies-based approach. A place to start is to note that all accredited programs, as part of the accreditation process, are required to prepare goals and objectives for their programs, to describe the competencies that give evidence of the objectives, to describe how these outcomes are assessed, and to summarize the findings of these assessments in reports to the CoA. However, program’s complying with accreditation requirements is not the same thing as faculty embracing the competencies approach as a core, organizing principle for the program and as a model for its everyday functioning. We recognize two general approaches to this process. Both begin with presenting an overall rationale for competency-based training and education as described above – the essentials are: the value of clearly articulating what we want our graduates to be able to do, of thinking through how our curriculum and training program can best achieve this outcome, and of considering how we can assess our trainees’ growing competence. Ideally the faculty will be ready for a full review of the curriculum on this basis, but if not it may be best to start more gradually, using the competencies rating forms as an aid in assessing trainee progress and outcomes, perhaps as part of the program’s attention to accreditation requirements. This would involve selecting from the competency rating forms those competencies, essential components, and behavioral anchors that match the previously established curriculum and goals. As faculty and/or supervisors become more familiar with the core competencies and more comfortable with thinking about and reporting on their trainees’ competencies, it may be possible to introduce the more system-wide application of the competencies approach.

Even with a willing faculty, one of the biggest challenges to implementing the competencies-based approach involves thinking of the curriculum as an organized, integrated, and coordinated sequence that develops in step with the kinds and levels of competence expected of the trainee. This requires shifting from “my course – what every trainee should know about X” to “how can my course best help trainees reach our overall competency goals?” A competency-based curriculum does not create courses for their own sake, but rather to assist the trainee in gaining the overall level of competence desired for program graduates. Trainees who wish to develop advanced skills in a given area (e.g., statistics) are encouraged to pursue electives. Medical schools and their faculties that have adopted this approach find that time-honored courses, with long-established expectations, are difficult for faculty to change. For example, anatomy has tended to be a course with a life of its own, with steadily advancing expectations on the part of the faculty that teach it. These faculty have struggled with the decision that trainees can achieve satisfactory competence with many fewer hours of instruction than tradition has called for. It may be difficult to make elective those currently required courses that reflect the special interests of senior faculty. Thinking through how each course could contribute to the overall competency goals of the program is also a challenge. How can a course in statistics address the multicultural competence? Professionalism? At the same time, this project can be exciting and innovative.

Similarly, rethinking the practicum program can pose challenges. These challenges may be primarily administrative in nature, at least to the extent that the program has already focused on how to best prepare trainees for the practicum, and have developed a good way to help trainees use their practicum experiences (e.g., through a concurrent practicum seminar) to enlarge their understanding of other key issues such as professionalism, self-care, and the integration of science and practice. How can the graduate program organize its practicum program so as to ensure that the sequence of practicum experiences optimizes each trainee’s learning and competency goals? This may require shifting from simply finding a practicum to planning a sequence of practicum experiences for the trainee.

If for whatever reason tackling this project seems unfeasible or ill-advised, Plan B focuses on assessing the competencies that reflect the goals of the current curriculum. The process begins with study of the Competency Benchmarks rating forms to determine which of its elements match the established goals of the graduate program. This approach does not ask faculty to question its curriculum; rather it asks faculty to think about the established curriculum in terms of how it would manifest itself in trainee competencies. Starting with the curriculum as currently constituted, faculty select those categories, competencies, levels of achievement, and behavioral anchors that match. If specific competencies are not found in the Benchmarks, new ones are written, along with behavioral anchors that fit. If the behavioral anchors found in the document are not properly attuned to the specific ways competencies are manifest in your program, new ones are written. This process should result in a set of competency rating forms that can be used in various ways throughout the program.