Many physicians consider electronic health record (EHR) documentation to be a main source of burnout. 1 In fact, recent increases in physician burnout have coincided with the widespread adoption and use of EHRs. Even among those who aren't experiencing burnout, it's rare to find a doctor who is not experiencing some degree of frustration with the EHR. Poorly designed and poorly implemented EHRs are to blame, and continued advocacy is needed to improve these problems. In the meantime, there are strategies all physicians can use to become more efficient with electronic documentation — strategies that can help reduce frustration, improve productivity, and reduce work after clinic.

While not every strategy described in this article may be applicable to your practice, and you may already use others, if you find even one or two new strategies to help you get home a little earlier every day, reading this article will be time well spent.

Before I began using my current EHR system, my documentation routine was to take handwritten notes during a visit. At some point after the visit, I would dictate the visit, which would later be transcribed for documentation. If I was running behind, it was very easy for those dictations to stack up. At the end of a shift, I might have a half day of documentation to complete. At the end of particularly busy days, I might have almost an entire day of dictations left to do. Seeing a tall stack of charts and many undictated notes on my desk was, by far, my least favorite part of thsse day. Completing those notes was the task I most dreaded.

Today, when I finish the visit, my note is done. Those days of stacks of unfinished records are just bad memories. I spend less time documenting, and I get paid for more of my work. In the past, if I used CPT time-based coding, I could not count the extra five minutes of dictating that I completed after the patient left. Now, because I do all my documentation with the patient in the exam room, any time that I do spend is potentially billable.

Here are 10 strategies that have helped me become more efficient and could help you too, no matter which EHR system you use.

1. Rethink your exam room setup. Ideally, you should place the computer where you can alternate between looking at the screen and looking at the patient with only a small shift in your gaze. There are a variety of exam room setups that will work (see the first photo below). The key is to avoid setting up the room so that your back is to the patient, because you'll lose the ability to pick up important nonverbal communication and you'll potentially get a sore neck from frequently turning your head. Having a laptop computer or a monitor that swivels makes it easier to show the patient information on the computer screen. Some practices even put their computer workstations on wheels and make them wireless so the entire setup can be moved around as needed.

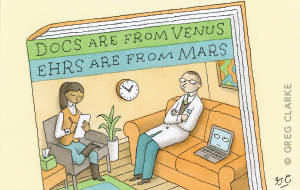

When you are doing a televisit, the best setup involves two screens — one screen (perhaps a tablet) that displays the patient and a larger screen that displays the EHR for documentation (see the second photo below). Again, with only a small shift in your gaze, you should also be able to change your focus back and forth between the patient and the EHR.

For a face-to-face visit, place the computer in a location where you can easily see your patient and your EHR screen without having to turn your head. Do not place the computer in a location where your back would be facing the patient. With the setup shown below, note that whether the patient is seated in the chair or on the exam table, only a small shift in gaze is needed to document in the EHR. I usually ask the patient to sit in the chair at first (further away) until the exam, which has been helpful during the pandemic.

For a televisit, use two screens (one with the patient and the other with the EHR) so you can easily shift your gaze back and forth as needed. In the setup shown below, the iPad is being used for video-conferencing. Note that the camera lens of the iPad is nearest to the computer used for documentation, so only a minimal shift in gaze is needed to look into the camera.

2. Maximize your use of templates and smart phrases. Templates should be used for physicals, routine office visits, televisits, procedures, patient instructions, specific parts of exams (e.g., knee exams), and lists of numbers (e.g., most recent blood pressure readings, weights, A1Cs, thyroid stimulating hormone levels). This eliminates the need to type out words or phrases that you use repeatedly. Learn how to quickly turn part of a note into a template, or how to insert smart phrases into your notes. Ask to use your colleagues' templates, download FPM's spreadsheet of smart phrases, or browse the sample templates and phrases I've created, all of which you can copy or modify for your practice.

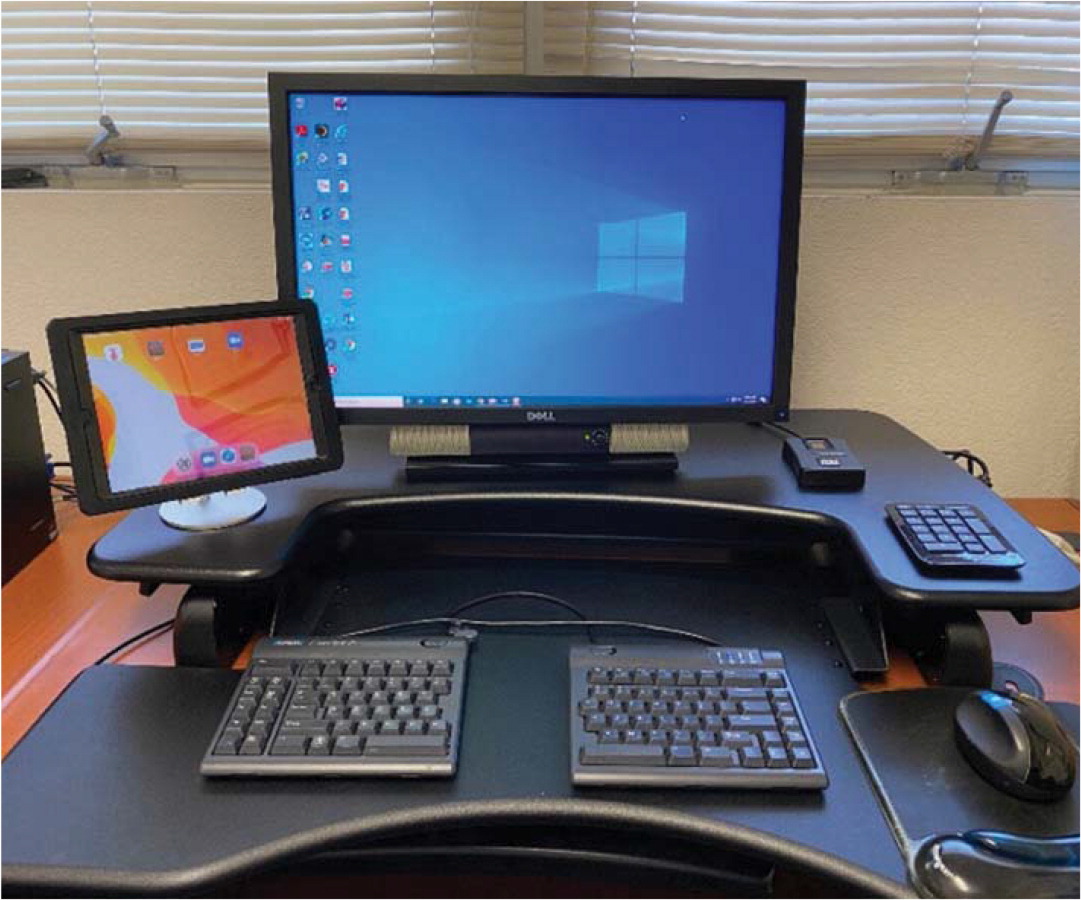

One of my favorite templates provides an automatic list of the patient's diagnoses and associated orders. I use Epic, but many other EHRs have this function as well. I can insert this template into the assessment/plan, and then I only have to type in a few details at the end to complete this part of the note (see “A sample template”).

The author's EHR offers a template that provides an automatic list of the patient's diagnoses and associated orders, which he inserts into the assessment/plan to reduce the amount of typing needed to complete this part of the note.

3. Learn to type quickly or use a typing assistant in the exam room. Typing skills allow you to document electronic notes as quickly as handwritten notes — with no additional time spent dictating after the visit. There are free online typing games to help you get faster and more accurate (just Google “free online typing game”). If you don't want to type, consider using a scribe or an extra medical assistant to help with documentation (more on that later in the article).

4. Document the history of present illness (HPI) with understandable notes. Do not type long paragraphs. It takes far too long to write the detailed histories many of us were taught as medical students, and your colleagues do not want to spend time reading your lengthy prose. Sentences are for novels and prisons, not for documenting a medical visit. Instead, for each complaint, type short phrases separated by a semicolon (the key directly under your right pinky finger on the keyboard), and when you need to document a separate complaint, move your pinky over two spaces and hit the enter/return key. (See the example, “Documenting the HPI: 637 characters vs. 153 characters.”)

| Don't do this: | Do this: |

|---|---|

| Mrs. Mary Wadsorth Smith is a very pleasant fifty-six-year-old female. She is married to another patient of mine, Mr. Robert Montgomery Smith, III. Robert has been concerned about Mary's headaches. They have been severe and frequent. They have been approximately nine out of ten in severity. The headaches are frontal in location and are preceded by a visual aura. The patient also has photophobia and phonophobia with the headaches. Although the headaches have been present for ten years, they are more frequent in the past two months. Now they occur every other day. Additionally, the patient has been having pain in the front of her left knee for the past two months. It has been particularly bad for the last two weeks. It bothers her more when she runs downhill. | Frontal HAs for 10 yrs; worse for 2 mos; now QOD; 9/10 severity; has visual aura, photophobia, phonophobia. Anterior left knee pain for 2 mos; worse for 2 wks; worse running downhill. |

5. Use the problem list to quickly document your follow-up of chronic problems. My templates for both office visits and physicals contain a problem list at the end of the HPI. Above the problem list is a short phrase: “Interval history in bold” (for the office visit template) or “In addition to preventive health, we discussed the following problems (in bold)” (for the physical template). If I need to take an interval history to follow up on a chronic problem, I make the problem list editable (a right-click with my EHR) and type brief phrases in bold. For instance, for the problem “diabetes with CKD III,” I might write “fasting FS ave 125; AC lunch ave 130; diet has been good except for Thanksgiving; brisk walking 30 min 4 days/wk.” I'll then type in my smart phrase that will pull up the patient's last few A1C results. Another option, if you cannot make the problem list editable or if you are only covering a couple of the items on a long list, is to write the documentation above the problem list. And if you don't have smart phrases for inserting recent A1Cs or other numerical data, you can simply copy and paste the data from the results section of your EHR. It is not necessary to cover everything on the problem list in a particular visit, of course, but these hints will help with documentation of the chronic problems that you do need to cover. (See the examples in “Strategies for HPI documentation.”)

| 1. Start with a basic template and record the chief complaint. The HPI portion of your template should also have a space for the acute problems and the problem list. | Chief complaint: 56 yo female presents for knee pain Subjective: Interval history in bold: Problem list: Type 2 diabetes with hyperlipidemia OSA on CPAP Essential hypertension |

| 2. Document the acute problems using short phrases. | Chief complaint: 56 yo female presents for knee pain Subjective: medial R knee pain for 3 mos; worse for 4 wks; no known injury but started running 4 mos ago; no redness; no fever; minimal relief from ibuprofen 400 mg Interval history in bold: Problem list: Type 2 diabetes with hyperlipidemia OSA on CPAP Essential hypertension |

| 3. Add the interval history by making the problem list editable (a right-click with my EHR), and document with short phrases written in bold. Alternatively, if unable to make the problem list editable, simply document the interval history above it. | Chief complaint: 56 yo female presents for knee pain Subjective: medial R knee pain for 3 mos; worse for 4 wks; no known injury but started running 4 mos ago; no redness; no fever; minimal relief from ibuprofen 400 mg Interval history in bold: Problem list: Type 2 diabetes with hyperlipidemia ave fasting FS 115; AC lunch 110; pc dinner 140; exercising regularly; taking all meds; healthy diet except vacation last week OSA on CPAP using CPAP 6 hrs/night; feeling less tired with it; no longer needs naps Essential hypertension taking meds daily; no dry cough; no rash; not lightheaded; BPs at home ave 135/84 |

| 4. Use smart phrases to insert the patient's recent numerical data (e.g., blood pressure readings and A1Cs). Alternatively, copy and paste numerical data from the results section of your EHR. | Chief complaint: 56 yo female presents for knee pain Subjective: medial R knee pain for 3 mos; worse for 4 wks; no known injury but started running 4 mos ago; no redness; no fever; minimal relief from ibuprofen 400 mg Interval history in bold: Problem list: Type 2 diabetes with hyperlipidemia ave fasting FS 115; AC lunch 110; pc dinner 140; exercising regularly; taking all meds; healthy diet except vacation last week 5/5/2019 A1C: 7.4 11/7/19 A1C: 6.9 OSA on CPAP using CPAP 6 hrs/night; feeling less tired with it; no longer needs naps Essential hypertension taking meds daily; no dry cough; no rash; not lightheaded; BPs at home ave 135/84 11/8/19: 139/86 10/1/19: 145/88 8/5/19: 135/82 5/7/19: 155/90 |

6. Use patient questionnaires to gather data. For a review of systems (ROS) or other common scenarios (PHQ-9, sleep apnea, adult ADHD screenings, etc.), instead of asking patients every question yourself, have your staff provide them with a brief questionnaire that gathers the data. For example, I use an ROS questionnaire that correlates with my ROS documentation template (both are available for free at https://stressremedy.com/primarycare). If patients have positive responses, I simply update the template, writing in the positives in bold so they are easy to see. I also use an online questionnaire that allows patients to submit updates to their medical history that I then approve. Online questionnaires, as opposed to paper-based questionnaires, are preferable because they can be used for both televisits and office visits.

7. If you use dictating software, take the time to train it. With a little training, the software will be much more accurate. For example, if the software consistently misrecognizes a word or a command, you can teach it the correct pronunciation or add words or phrases to its vocabulary. You can even train the software to add templates using voice commands. It's time well spent.

8. Streamline patient education. One way to do this is with “copy and paste.” Simply copy parts of the plan (written in lay language) and paste them into the patient instructions. This saves you the time of having to restate and retype the information. Some doctors also speak their instructions out loud to the patient as they type the plan, which provides additional reinforcement.

Another time-saving strategy is to utilize audio or video patient education materials during the visit. For example, if a patient is anxious and I've recommended meditation, I might have the patient listen to a short meditation (see https://stressremedy.com/audio/ or https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8HYLyuJZKno) while I finish writing the medical orders. Or if a patient is suffering from panic attacks and I've recommended a video on dealing with panic and anxiety (see https://stressremedy.com/videos), I might have the patient watch the video while I see my next patient. Then I can come back and finish the visit by answering the patient's questions and collaborating on a final plan.

9. Get help from a superuser or EHR staff. When you feel like you're drowning in computer work, the last thing you might want to do is spend more time working on the computer. However, a little investment in technical education, optimizing your system, or learning the hints that others use can really pay off.

10. Consider using a scribe or team documentation. Primary care offices have typically employed one medical assistant per physician, but some practices have begun utilizing additional staff to help with electronic documentation. Depending on your practice style, practice setting, and comfort with your EHR, using a scribe or team documentation may be extremely helpful. Physicians who use a scribe or team documentation generally are more productive (and get home earlier), and the increase in productivity outweighs the extra staffing costs. For more information, see the FPM article “Team-Based Care: Saving Time and Improving Efficiency,” the American Academy of Family Physicians TIPS resource on team documentation, and the American Medical Association's Steps Forward module on team documentation.

Some of the strategies I've suggested in this article can be implemented immediately in your practice, while others will require more effort. Don't get overwhelmed thinking you have to implement all of the strategies at once. Just pick one to get started. Any time and effort you spend now will pay off later, and eventually you'll have the satisfaction of ending each visit and each workday with your documentation complete.